After the luxury and glamour of Champagne, it was time for a much more serious stop. If you missed our previous posts, you can find the first post here. You can also read our previous post here.

Ypres today is a quiet little town, but during the First World War it was the epicentre of some of history's most devastating battles. As we rolled the motorhome in through the beautifully rebuilt streets, however, it was hard to imagine that this place once lay in ruins, surrounded by mud, trenches and constant artillery fire.

For those who are not interested in the historical background, click here.

Background

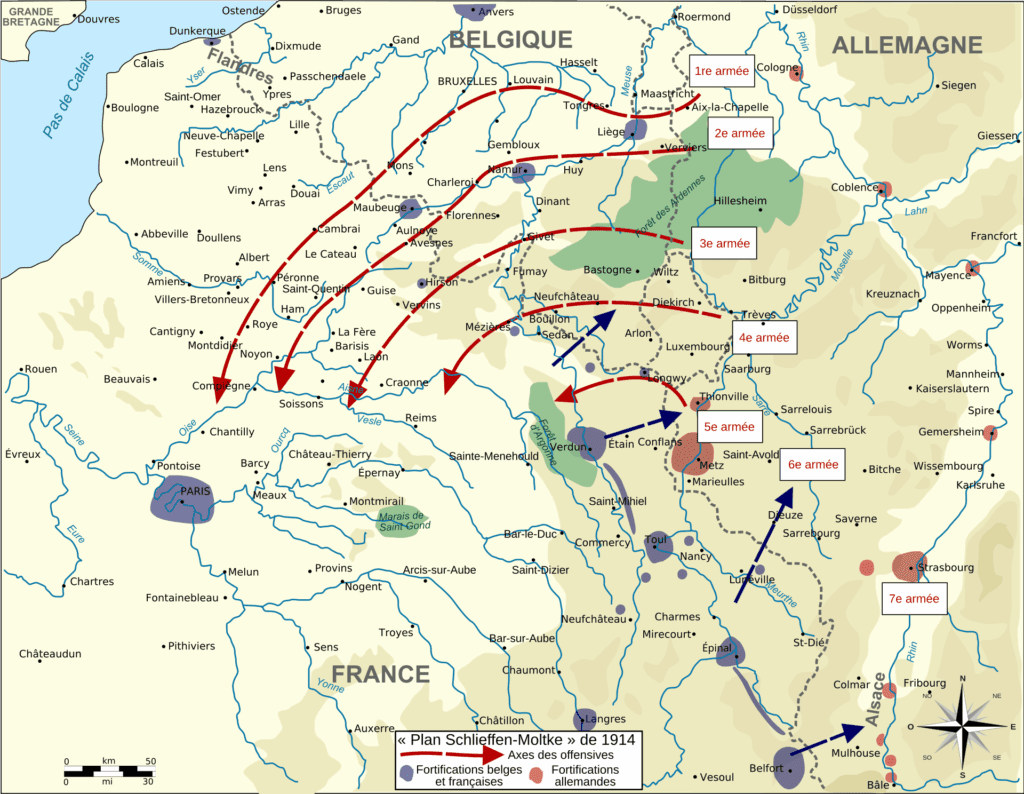

For those of you who don't know what happened here, it was a key theatre of war during the First World War. When the Germans entered the war and activated their Schlieffen Plan, the Allies were caught off guard by the rapid advance. As a result, they were unable to organise a proper defence until the Marne River, deep in France.

As neither side had enough strength to break through the front line, the race to the sea began, which basically meant trying to get round the front line to attack on the flank. The front line moved further and further west in this way until it was finally almost all the way out to sea.

In this area were the remnants of the Belgian army, which so far in the war had put up an unexpectedly stiff resistance to German superiority. But with the entire German war machine focussed on breaking through their lines, they could not hold out any longer. In a last desperate attempt to stop the advance, the sea defences were destroyed and much of western Belgium became a lake.

After this dramatic change of scenery, Ypres suddenly became a strategic location as it was the only route to the harbour towns of Dunkirk and Calais. If the Germans were to take these towns, they could virtually cut off the British expeditionary force from the homeland, perhaps forcing them to leave France or at least making life difficult for them. In other words, both sides had a strong incentive to hold the city.

The area became known as the Ypres Salient and despite numerous attempts to take the town, the Allies managed to hold it throughout the war. For years, the defenders were exposed to fire from three directions and the Germans also had control of the surrounding hills. Winston Churchill said after the war:

"I should like us to acquire the ruins of Ypres....a more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world."

However, it came at a terrible cost, with an estimated 1 to 1.5 million people injured or killed. Part of the reason we don't really know is the soil, which may sound a little strange. The soil here is largely clay, and after the dams to the sea were opened up, the water had nowhere to go. This, combined with non-stop artillery fire, was the perfect recipe for turning everything into one big mud puddle. In many of the great battles, thousands of people simply disappeared into the mud and to this day, farmers and builders still find the remains of those lost souls.

The Third Battle of Ypres, also known as Passchendaele, provides a frightening illustration of this problem. In July 1917, the Allies were about to make a major coordinated advance and, as always, the attack began with intense artillery fire. During the initial phase, it started to rain, turning the whole place into a death trap. The troops could only advance on narrow tracks under constant artillery and machine-gun fire. For the poor souls who fell off the footbridges, a cruel death awaited as they slowly sank into the mud until they drowned. A few months later, when they finally managed to take the small village of Passchendaele, it was at a cost of over 250,000 wounded and dead. The German side did not fare much better and lost about the same number of soldiers in the fighting.

Perhaps most tragically, a few months later the city was lost again, in what is commonly known as the Fourth Battle of Ypres. The Germans had just concluded a ceasefire with the Russians and, in the process, moved half a million troops to the Western Front. In a last desperate attempt to break the Allies, they gambled everything on one card. The decision was also fuelled by the fact that the Americans had just declared war and the Germans knew they wouldn't stand a chance when the American troops arrived in Europe.

Another famous battle is the Second Battle of Ypres. This battle was characterised by the first large-scale use of gas, for which the Allies were completely unprepared. Complete panic ensued and after a few days of fighting, almost 10,000 people had lost their lives to chlorine gas. Another effect of this was the start of an arms race in which more advanced methods of both attack and defence were developed.

Humans have always been very creative when it comes to finding new ways to kill each other. At 3.10am on 7 June 1917, the British Prime Minister was awoken by a dull rumbling sound. He initially thought that London was under attack but after consulting the War Office, he learnt that it was the result of the Allies having just blown 19 tunnels under the enemy as part of the conquest of Messines Ridge. The ridge was of great strategic importance as it offered a view of the whole of Ypres and the surrounding area. The total amount of explosives was 455 tonnes spread over 8000 metres of galleries. Until the testing of atomic bombs, this was the largest planned blast in history.

The effects were of course devastating. More than 10,000 German soldiers died directly from the blast, and of those who survived, they were either injured or completely disorientated. There are stories of how German soldiers embraced the Allied soldiers while others just sat in the rubble and cried. The pictures below show the effects of similar explosions. To put it all in perspective EN of the 19 explosions in a crater 72 metres wide and 12 metres deep.

Another aspect of this is, of course, the challenge of caring for all the wounded and dead people. To put it bluntly, a dead soldier is a relatively minor problem, while an injured soldier is a strain for days, months or years. Yes, in the worst case, it is something that society has to deal with for the rest of the person's life. Given that the number of injured is estimated to be close to one million, you can imagine the apparatus required to administer this.

This, on the other hand, was an area where real progress had been made in recent decades. It all started fifty years earlier with Florence Nightingale's success in getting doctors to wash their hands, which in turn led to a completely different approach to hygiene and sterile environments. In a world where antibiotics did not yet exist, this was even more important as a relatively minor infection could be fatal. This revolution in medical care meant that wounded soldiers had a much better chance of recovery than they had fifty years earlier. However, there were no guarantees, as we saw very clearly when we visited a hospital cemetery in the area. More on that later in the post.

There were no significant differences between nations and a somewhat simplified explanation is that care was divided into field, frontline and home hospitals and a number of different ways of transporting patients. Note also that only the worst injured ended up in hospital. If you had minor injuries, you were patched up at your post and then quickly sent back to duty.

The city centre

But let's get back to the present. Ypres today is a beautiful town dominated by a large square. There are many beautiful buildings here, including the famous Cloth Hall, whose predecessor was a result of the very lucrative fabric industry that made the village rich. I say predecessor because you can see in the pictures above that basically everything had to be rebuilt after the war. A slightly amusing effect of this is that many of the residential buildings look more British than French.

Another thing we may have to sort out is the spelling. You will have noticed that the French and British say Ypres while the Germans use Ypres, but as the town is, after all, in the Flemish part of Belgium, we think you should use their spelling, which is Ypres.

Cloth Hall, today contains a tourist office as well as two museums, In Flanders Fields which is about the First World War and a museum about the history of Ieper. We only visited the first of the two and it is the most interesting museum I have been to. This is coming from someone who is very interested in history and has been to war museums all over the world. What really sets this one apart is that they've focused on the man in the war rather than technology and big battles. Add to that the fact that they use the latest interactive technology and you have a recipe for success.

The description says that the museum should take one to one and a half hours. We were there when they opened at 10am and when it started to get close to lunch we had to run and put in more parking money as we only got half way... 😛

From the tower of Cloth Hall you also get a nice view of the city. The picture at the beginning of the post is from there but you can also see the big cathedral. There are of course lots of other things to see in the city but I would still say that the museum is the absolute highlight.

The Last Post and Menin Gate

An absolute must when visiting Ypres is to witness The Last Post, a daily ceremony in memory of those who died in the First World War. It has been held every day since 1928, making our visit number 33648. Every day may not be entirely accurate as there was a break during the Second World War when Belgium was occupied. For some reason, a former Lance Corporal from the First World War thought there was no need to be reminded of this. As I understand it, he served as an orderly in Belgium and, if his description in Mein Kamp is to be believed, he was unhealthily bitter about the defeat.

Regardless, The Last Post is a very special experience that should not be missed. The first thing that surprised us was the amount of people gathered. We were there before the tourist season started and yet it was completely packed half an hour before it started. In other words, you should be there in good time to see something of the ceremony. Another thing that struck us was how thousands of people can be so quiet. Despite the large amount of schoolchildren, it was really quiet and just sharing this moment in silence was very special.

Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery

Around the city there are lots of memorials, cemeteries, museums, trenches, etc. It can be difficult to get an overview but if you want to be sure not to miss anything, I can recommend the book, "Visiting the Somme and Ypres Battlefields Made Easy" by Gareth Hughes. It gives detailed descriptions of the whole area and also has suggestions on how to ensure that a group gets the most out of the trip. There are even suggestions for stories to tell at different times to give the group a more dramatic experience of the sites.

Our plan was to spend the whole next day visiting various sites and museums but as the rain was pouring down we decided to move on. After reading all about the hardships associated with the Belgian mud, we weren't super keen to experience it first hand...

However, we made a stop at a memorial site that was on the way, Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery. There was also a small museum where we learnt that this was a hospital cemetery, in other words it was people who hadn't made it despite receiving care.

The hospital was the largest in Ypres and had at most 4000 beds. We understand that an unusually high proportion of pilots came to this hospital. The exhibition therefore focussed on both the hospital and the special role of pilots during the First World War.

What I found particularly interesting was how they organised the care and transport of the sick. You can imagine the organisation it took to take care of over a million injured people who passed through the care chain, just here in Ypres. It's a bit difficult to find reliable statistics on that but one figure I saw is that the British transported 750,000 patients from France to England in 1916 alone. That includes the whole of the Western Front but not all the other countries that took part in the fighting, nor those who didn't come home at all.

One person who contributed greatly to the emergency care of soldiers was Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel. He was a highly respected doctor in the United States who returned to his native country when war broke out. Few have done as much as he did in developing new ways to treat seriously injured soldiers.

In addition to the museum, there is also a large cemetery. One might think that with its 10786 graves it should be the largest, but Lijssenthoek is actually only second, as Tyne Cot Cemetery, is even larger. There are also a large number of other cemeteries in the area, both for the Allies and for the central government. Many of these sites also harbour missing soldiers who never received a burial. An example of this is Tyne Cot, where there are memorials to over 35,000 people.

Other places to visit

As we mentioned above, there are a lot of places to visit and it is good to do a little research before you go as it is difficult to fit everything in. Some worth mentioning are the Passchendaele Museum and the Sanctuary Woods Museum which are both well worth a visit. As the name suggests, the latter is located near Santuary Wood where they have also preserved trenches from the war. There is also Hill 62, which you may have read about.

What to do when it rains?

After all those horrors we learnt about in Ypres, it's important to remember how good we have it here and now in modern Ypres. We therefore spent a lot of time just sitting and talking to each other and cooking some food in the campervan. Normally we often indulge in a good restaurant, but the rain combined with the experience made us feel more like a bit of home cooking. A little local pick for dinner and of course Belgian chocolate for dessert. You have to take the custom where you come... 😉